How I Accidentally Wrote My First Book with AI

Part 3: Publishing — Where the Illusion of Done Fell Apart

In Part 1 of this series, I described how I accidentally gave myself five weeks to write, edit, and publish my first book — and why I turned that constraint into an experiment using AI as scaffolding rather than a shortcut. In Part 2, I walked through how editing became the most demanding phase of the project, and how using different AI tools for structure, clarity, and line editing made judgment sustainable without replacing it. This phase picks up where that work ended — when the words were done, but the book wasn’t.

Introduction

After writing and editing, I assumed publishing would be the easy part.

The thinking was done. The words were there. How hard could it be to turn a finished manuscript into a book?

That assumption was wrong — in a very different way than the others.

Writing and editing are creative problems. Publishing is an operational one. And that distinction mattered more than I expected.

If you want to catch up on how the writing and editing came together, the first two parts of this series are a good place to start.

Two paths to the same book

Publishing The Doodle Principle meant producing two different artifacts from the same manuscript:

A Kindle ebook, created using Kindle Create

A print-ready PDF, built in Microsoft Word for the physical book

On paper, this sounded straightforward.

In practice, they exposed two different kinds of friction — and two different limits of AI assistance.

Kindle Create: when control becomes the problem

Kindle Create was the most frustrating part of the entire project.

Not because it’s a bad tool — but because I kept trying to use it the wrong way.

Coming from a program management and documentation background, I’m used to controlling layout precisely. Fonts. Spacing. Line breaks. Page flow.

That instinct worked against me here.

Kindle ebooks are reflowable. The reader’s device, font size, and preferences determine how text appears. The author gives up a lot of control by design.

AI tried to help me troubleshoot formatting issues — but it kept answering the questions I asked, not the problem I actually had.

An experienced human would have said this immediately:

You’re trying to control something you’re not supposed to control.

Once I stopped fighting the tool and understood its constraints, things improved. But getting there took far longer than it should have — and AI never quite surfaced that big-picture insight on its own.

Publishing as an operational problem

Writing and editing are creative problems. Publishing is an operational one.

Creative problems tolerate ambiguity. You can experiment, revise intent, and change direction. Voice matters. Judgment matters. There’s room to be “mostly right” while you discover what you’re actually trying to say.

Publishing doesn’t work that way.

Publishing is about fitting content into an established system of rules and constraints — many of which exist for reasons that aren’t obvious until you violate them. Kindle ebooks are reflowable. Physical books are fixed. Margins, headers, footers, page numbers, and section breaks all have to conform to both printing requirements and reader expectations.

There’s very little room for interpretation.

Page numbers need to appear where readers expect them. Front matter (title page, credits, table of contents) follows conventions most readers never consciously notice — until something feels off. Chapters need to start cleanly. Margins aren’t aesthetic choices so much as physical necessities.

In other words, publishing isn’t about expression. It’s about compliance.

That shift mattered. The instincts that helped me while writing — experimenting freely, refining ideas as I went — often worked against me during publishing. I didn’t yet understand the system I was working inside.

AI was good at explaining how to do specific things within that system. It was much less reliable at helping me understand the system as a whole.

PDF creation in Word: precision by accumulation

Building the print-ready PDF in Microsoft Word was more successful — but also more iterative.

AI gave me accurate, step-by-step guidance for specific tasks:

Creating section breaks

Using lowercase Roman numerals for front matter

Switching to Arabic numerals for the main text

Starting chapters on new pages

Managing headers, footers, and page numbering

The issue wasn’t correctness.

The issue was orientation.

Each answer was right — but narrow. I often discovered the next requirement only after fixing the previous one. In several cases, I realized something was off only after pulling other nonfiction books off my shelf and checking how they handled the same detail.

A human editor would have explained the entire structure up front: how front matter works as a system, why section breaks matter, and what conventions readers subconsciously expect.

AI got me there — but through iteration, not overview.

Where AI helped — and where it didn’t

AI did shine in a few important ways.

It clearly explained the differences between fiction and nonfiction formatting. It helped me understand which layout details mattered to readers and which ones didn’t. That guidance saved time and prevented some avoidable mistakes.

But publishing exposed a clear boundary.

AI can tell you how to do something.

It’s less effective at telling you why the system works the way it does — or when you’re solving the wrong problem entirely.

The cover: prompts, patience, and taste

The cover process was the most collaborative part of publishing.

ChatGPT helped refine the language of my image prompts. Producing the images took a lot of trial and error. Grok produced images that came closest to what I had in my head — after significant experimentation. DALL·E, Gemini, and other generators missed badly.

Claude was especially helpful in critique mode. It pointed out moments where the title and subtitle were competing for attention and where spacing and hierarchy could be improved. Those weren’t technical issues — they were judgment calls — and that’s where AI worked best as a second set of eyes.

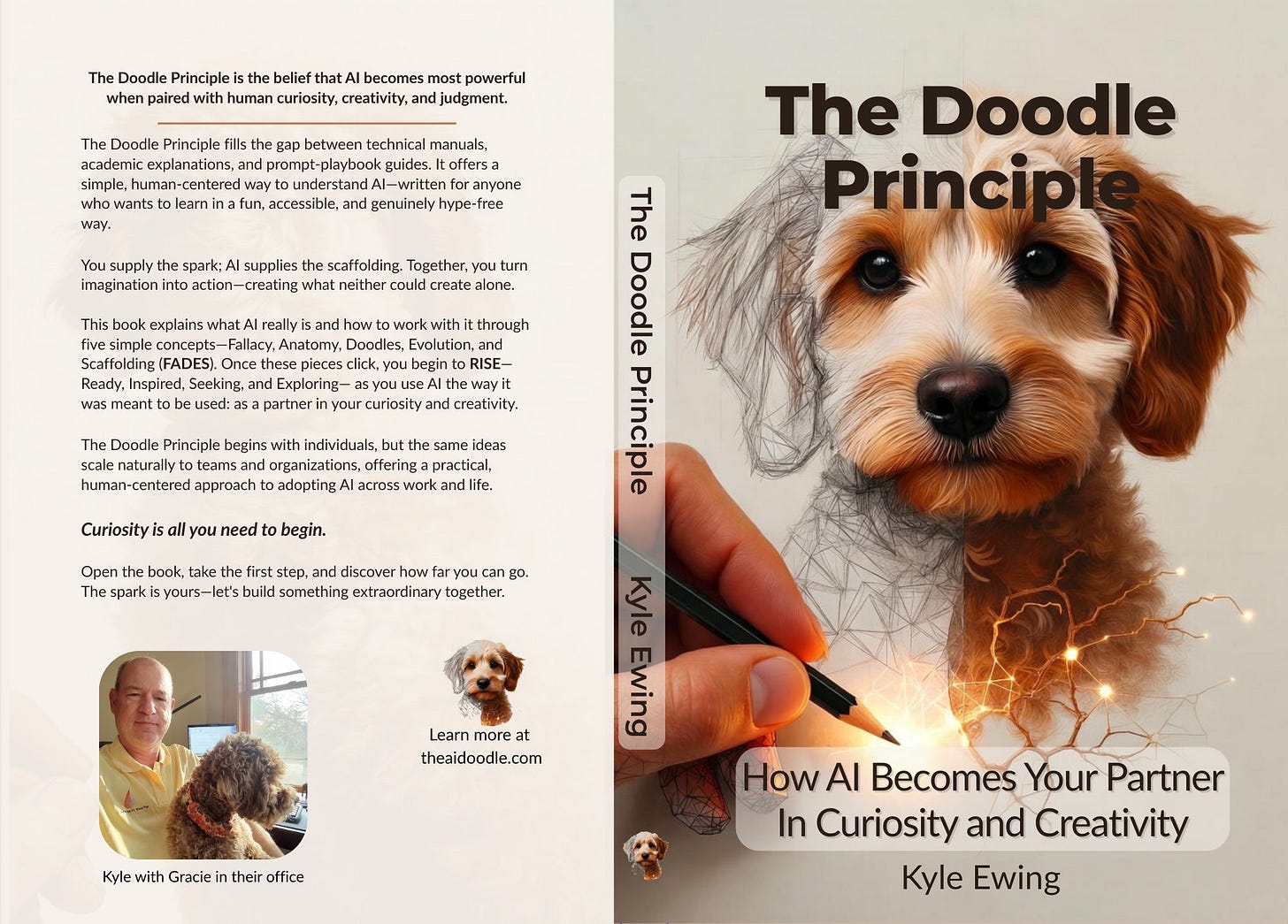

The cover image for this post comes from the AI-assisted process I used to create the book’s cover.

The pattern I didn’t expect

Looking back, a clear pattern emerged.

AI was strongest when:

The task could be decomposed

The rules were explicit

Iteration was cheap

It struggled when:

The problem required a holistic understanding of the process

The “right” answer depended on convention or taste

The fastest solution was the simplest—telling me not to try to control something

That pattern repeated itself several times during publishing.

The lesson from publishing

If editing taught me that judgment is the real work, publishing taught me something else:

Context matters more than instructions.

AI didn’t teach me how publishing works. It helped me survive learning it.

As scaffolding, it did its job — temporary, imperfect, but enough to get the structure standing.

What comes next

The final article in this series will be practical rather than reflective.

I’ll share the actual prompts I used across writing, editing, publishing, and cover design — not as a recipe or a guarantee, but as scaffolding.

The same kind that helped me finish.

The ideas and concepts in this article are the author’s own. AI assisted with ideation and editing.